RUSI's current membership is made up of men and women of different ages, professional backgrounds and nationalities. This was not always the case, however. When we were established in the early 19th century as a naval and military museum and library, there were restrictions on who could join. The accessibility of the Institute has changed considerably over the last 200 years, reflecting changes in attitudes, laws and technology. Perhaps most surprising, though, is what has stayed the same. The core of who we are and how we operate is still very much in the spirit of what our founders described. Furthermore, having a headquarters on Whitehall is still a necessity, despite major national crises. The bombing of London during the Second World War and a pandemic which revolutionised human interaction have not diminished the importance of the in-person experience.

At our founding in 1831 it was declared that:

The chief aim of this Institution is to foster the desire of useful knowledge amongst the members of the United Service, and to facilitate its acquisition at the least’ individual or public cost. …It is intended to be strictly a scientific and professional society, not a club. Neither politics, gambling, eating nor drinking enter into its design, from which the two former are absolutely excluded on principle, the latter as interfering with the established objects of the United Service Clubs.

RUSI’s Founding Committee

The Royal United Service Institution 1831–1931

RUSI still honours its founding principles and ethos. We continue to engage in rigorous academic debate; as a charity we are not-for-profit and impartial in our output, and our newly refurbished building has not been updated to include a bar (to the disappointment of some, perhaps).

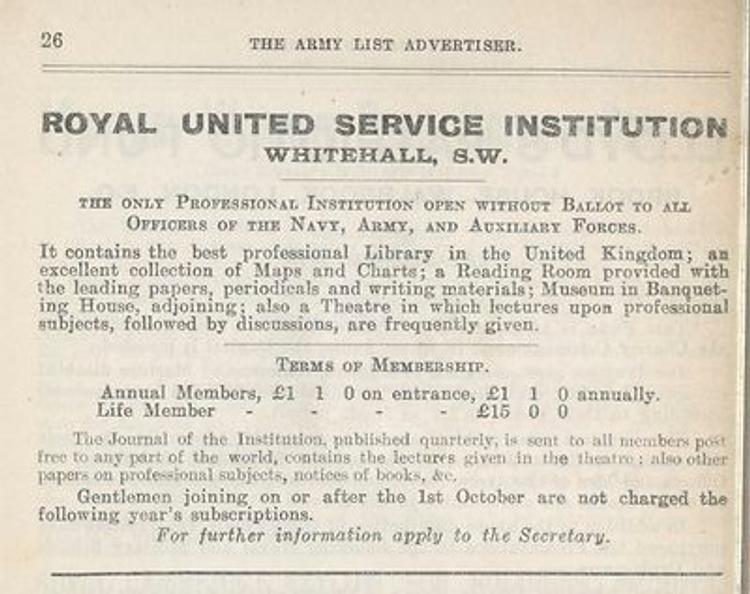

However, a reality not articulated by our founders - which would have been implicit - is that the people who walked through the doors of our first headquarters to listen to lectures, discuss and debate were from a very narrow demographic and social background. They were all men, British and officers from the army or navy. This was due to women rarely being found in the workforce, the UK not being as ethnically diverse as it is now and the restrictions on which professions could join as members (not to mention the aeroplane not having been invented yet). Additionally, only those from wealthy families were likely to be literate and able to climb the ranks of the military. RUSI was, as a result, very much an elitist organisation. Explorers Sir John Franklin and Sir Francis Beaufort, and even some members of the Royal Family, are all recorded as being members.

Change occurred in line with societal shifts at the time. Education became a provision of the state in the early 20th century, enabling progression in the military for those from different backgrounds. This in turn made RUSI more accessible. Not all events during this period were positive, however. The First World War was a painful time for the Institute, with over 500 members killed. In 2014, an article was published in the journal entitled 'RUSI's Roll of Honour, 1914–18' listing everyone who died. Eight of those men were awarded the Victoria Cross.

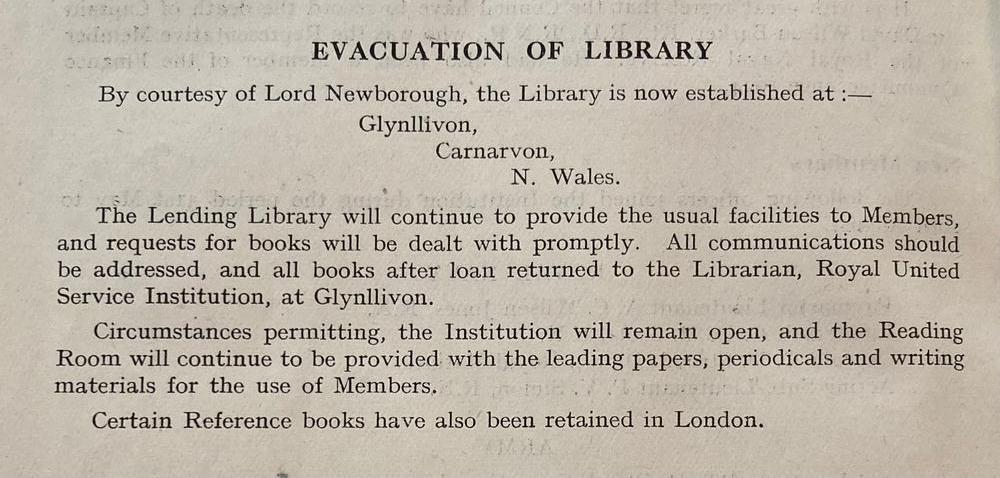

During the Second World War, special measures had to be taken to protect the building’s assets. Notably, the library was relocated to Wales. However, RUSI members could still borrow items by mailing in their requests. The decision was vindicated, as by 1941 around 140 bombs had been dropped on Whitehall. Interestingly, the Institute remained open for other member activities, and people continued to visit. Presumably it was calculated that it would be easier to evacuate people at short notice than 30,000 books.

One consequence of the World Wars was that attitudes to women in the workplace irreversibly changed, as they had proven themselves more than capable in a variety of jobs. RUSI responded and allowed women to join in 1942, over 100 years after our founding.

Being an officer in the military stopped being a requirement for RUSI membership by the 1980s. Even though our roots are in the study of military sciences, it is only one part of what we do. There are now an additional eight research groups looking at a variety of evolving and emerging security challenges, such as countering terrorism, finance and security, cyber security, nuclear proliferation, organised crime and more.

Many members prefer the in-person (and arguably ‘traditional’!) experience of visiting our building on 61 Whitehall, which was purpose built for us in 1895. However, with technological advancements, there are now a range of ways to access our work. A significant proportion of our lectures and conferences are hybrid or fully online, with a fast-growing repository of event recordings available to members. All our publications are available electronically, including the historic (and still very much active!) RUSI Journal, which dates back to 1857. We now engage with people from almost every country across the world, something which would have been unimaginable to those at the Institute in the mid-19th century.

The biggest change at the Institute has not been our purpose, but our people. While proud of our heritage and long scholarly tradition, RUSI recognises that to produce world-class research, diversity of thought must be a core value. This means inviting people from all backgrounds through our literal and virtual doors.

We hope that whatever way you participate, and from whichever part of the globe, you enjoy being a part of our continuous evolution.